The election of the German Bundestag 2025-2-23 has brought about many changes to the 1st chamber, the national parliament. First the voting system had changed to limit the newly elected parliament to 630 seats for a total of about 60 million people entitled to vote. 50 million voted in the election. The national average of participation in the election reached a very high 82.5%, with a range from 73.5% to 88%. Overall, it has been the highest participation rate since reunification. Political parties have to pass a barrier of 5% to be eligible for seats in the Bundestag. This regulation had been installed to avoid too many small parties to enter the Parliament as coalition building could be rather difficult and lengthy.

2 political parties missed this barrier closely, one with 4,3 % and another one with 4,97% of votes in the so-called 2nd vote, which is the vote for proportional representation in parliament after which the seats are allocated. Adding those ballots casts together, this means that for these 2 parties about 4.5 million votes do not get any representation at the national level. Several other smaller parties add more than 1 million votes, which are finally without any national representation. However, the only regionally campaigning conservative party from Bavaria reached 3 million votes (6% of votes) on the national level, which gives them a representation of 44 seats in the Bundestag.

Participation across age groups follows a relatively constant pattern. Older votes 60+ have relatively high voter turnout, whereas the younger age groups do not use the chance to vote as much as other age groups. This remains a challenge for democratic representation. The youngest have the longest time spell to live with the consequences of democratic representation and resulting policies. There are useful debates to lower the current legal age (18) to 16 years of age for voting to soften the effects of aging societies voting. Children, or currently anybody under 18, have no impact on political representation. An overweighting of families with children might fix such deficits. If the number of children drops further, we might eventually be willing to give our future a stronger voice in political elections. (Image: empty Berlin playground 2025)

Deutsch Deutscher

In English grammer we use comparative adjectives to express that something or someone has changed or undergoing change. Germany might have become more German. The second usage is to make comparisons not only between two points in time, but between two statuses or of two artefacts more generally. The statement “Deutschland wird deutscher”, therefore, intends to describe an ongoing process or the transition process from one state to the other. This statement as such does not offer any explanation or definition of the original state, nor of the second point of reference. It might just describe the dynamics or the direction of the dynamics. In this example it deals with social dynamics. Germany in the 21st century is posing more questions about its identity and future directions than some time ago. The artist Katharina Sieverding has put up this reflection as a poster on walls to provoke discussions about the way to identify and deal with German identities in the early 1990s, shortly after re-unification of the 2 parts of Germany (Image below from “Nationalgalerie für Gegenwartskunst, Hamburger Bahnhof, Berlin” 2024-5).

30 years later we are scared by a ruthless right-wing extremist and brutal movement that takes to the streets and commits crimes.

It is no surprise that the Higher Administrative Court in Cologne has confirmed that the “BfV’s classification of the party AfD and of its youth organisation as a “Verdachtsfall” (subject of extended investigation to verify a suspicion) as well as the publicising of this classification to be lawful“.

It is a step ahead to become “deutscher” if we battle out such decisions in courts rather than by force on the streets, although this has failed once in German history already. The poster action by Katharina Sieverding is a reminder to monitor and deal with these topics continuously, albeit the knifes may be coming in closer than before. Being frightened is no option in order to defend democratic values.

Sprachpolitik

Auf der internationalen Industriemesse in Hannover #HM19 wurde auf dem Pioneer Summit am 2.4.2019 wieder überraschend viel Deutsch gesprochen. Dem EU-Kommissar Öttinger auf Deutsch zuzuhören ist erfreulicher als auf Englisch. Der Vortrag von Klaus Helmrich, immerhin Mitglied des Vorstands der Siemens AG auf Deutsch zu folgen, ebenfalls bereichernd. Der unglückliche englischsprachige Titel “Thinking industry further!” kann man sich mit Industrie weiterdenken zurecht reimen. Genauer war dann der Untertitel: “Die nächste Stufe des Digital Enterprise”. Von “Made in Germany” sind wir längst zu “engineered in Germany” übergegangen. Aber das war Industrie 3.0. Bei der Industrie 4.x spielen vernetzte Standorte der Produktion, Entwicklung und Kunden eine zentrale Rolle. Sprachpolitik kann hierbei zu einem kleinen und bescheidenem Sicherheitsvorteil werden. Übersetzungsfehler von Längenmaßen (inch in centimeter) oder anderen Details verursachen kostspielige “Engineering Disaster” wohl auch bei AIRBUS industries aufgetreten.

Einigen Diplomaten und Journalisten zufolge wird selbst in der EU Kommission seit dem Brexit-Votum bereits mehr in anderen Muttersprachen geplaudert, zumindest in den Kaffeepausen. Willkommen in der alten, Neuen Vielfalt. Sprachen und Kulturen Verstehen lernen lohnt sich wieder.

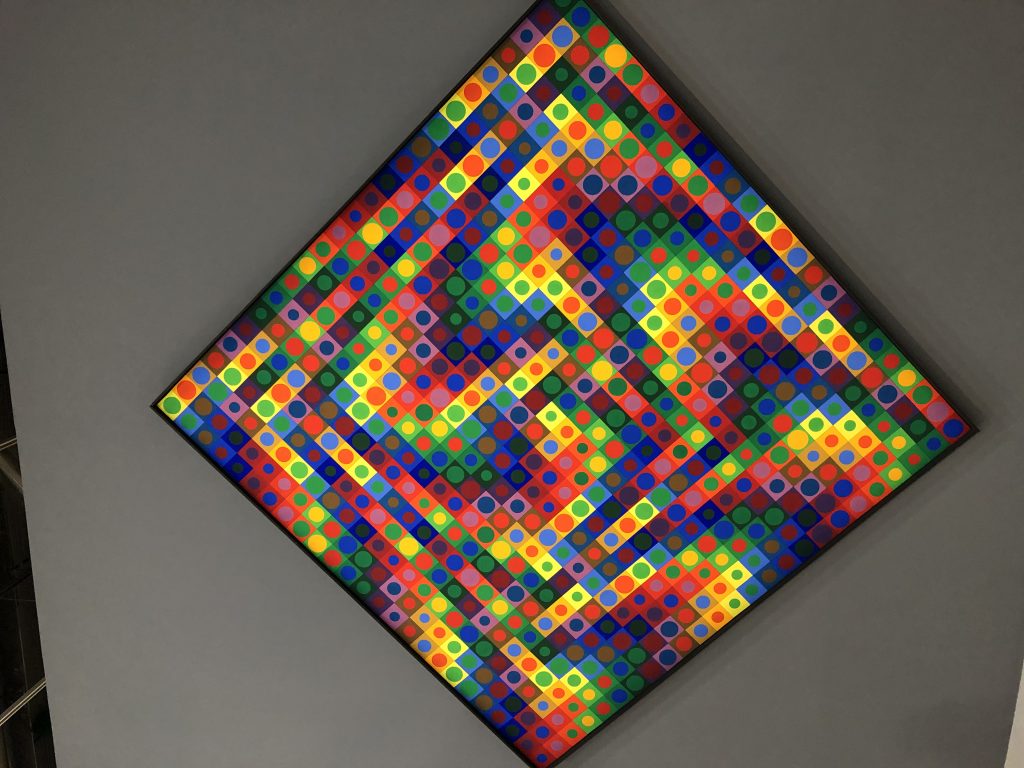

Bild von Victor Vasarely copyright http://www.fondationvasarely.org/ mehr Informationen zur Person https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Victor_Vasarely

Ausstellung noch bis 6.5.2019 im Centre Pompidou