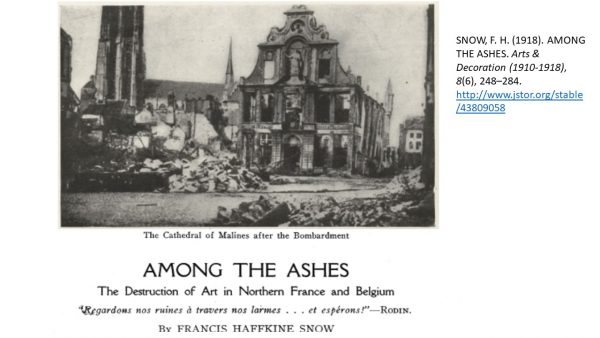

The right to publish without censorship is one of the first rights that suffers during wars. This has been the case since warfare has used communication as a strategic weapon. Therefore, it is important to research the often, subtle forms of control and censorship applied before and particularly during each war. The printed press was the prime target due to the scope of readers that can be reached timely and repetitively. From the history of how to silence critical voices we can learn about the proceedings, which even today find lots of authoritarian regimes copying these methods.

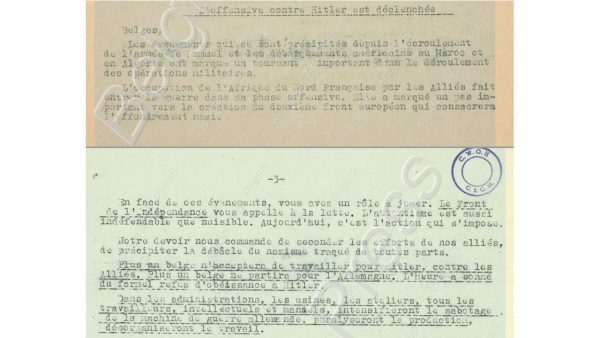

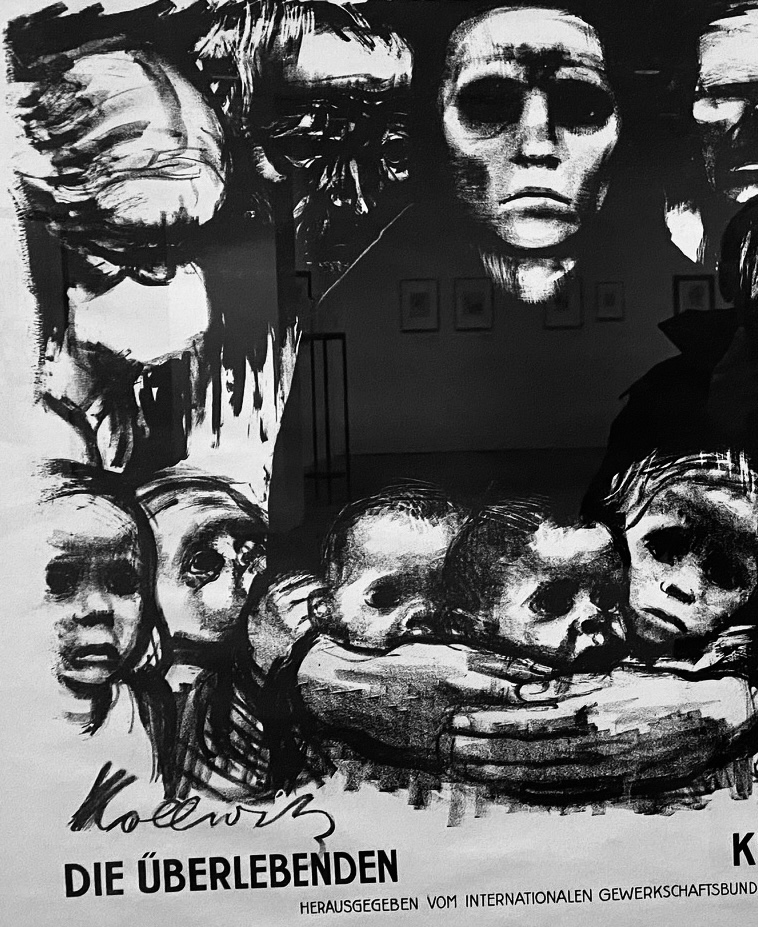

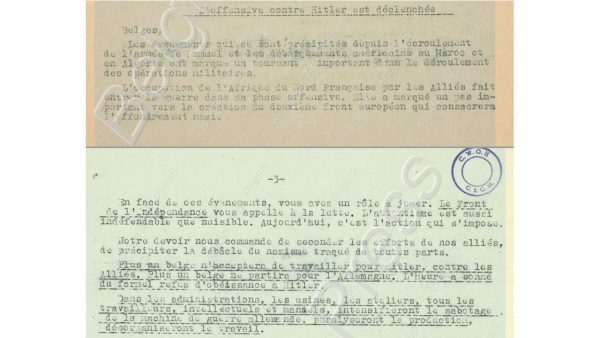

Using many illustrations from the 1st and 2nd world war in Belgium, 3 major forms of resistance to censorship become apparent. (1) The most obvious is closing down a newspaper rather than endure censorship and thereby being forced to contribute to war propaganda. (2) With risk to their own life, many people in the resistance movements relied on information to actively counter the worsening conditions of life and oppression of opinions or criticisms. (3) The third way at these times consisted in quitting the active contributions, but it incurred the danger that in fact the newspaper continued to appear as before, although with lenient journalists and editors. Today we would frame the latter form of continued appearance of a journal as “continued as fake news”. However, the issue is more complicated than that. Apparently, the readership needed still access to vital information of how to get access to food stamps or other day-to-day necessities including distraction from the horrors of war as it became an enduring feature of life.

This is my short summary of the inspection of some of the historical newspapers that are available with online access and the most valuable summaries provided by Emmanuel Debruyne and Fabrice Maerten in their blog entries on the overview pages linked to the “Belgian War Press” project. These are also valuable sources that hint at war crimes committed at these times as the collaborating press did not shun away from bragging about crimes. The clandestine press was also important to coordinate the various resistance movements and spread ideas of how contributions could be made to weaken the occupying criminal forces.

At times of communication via internet, in addition to the printing press, the war of communication needs much more resources above all digital-savvy resistance movements. A huge task to train people time to enable them to identify fake news and careful exercise of spreading correct and verified information nowadays.

Image Source: Extrait du « Bulletin Intérieur du Front de l’Indépendance », daté 15-11-1942, CEGESOMA BG85, Brussel.