The depiction of Marc Aurel as Emperor has become a trade mark in the history of art and politics. As an emperor with good horse riding skills, Marc Aurel was the first emperor to be portrayed as riding on a horse without saddle whilst, of course, in perfect skill to master the horse and give orders or strategic commands. Many subsequent emperors, Napoleon or Friedrich have had their power positions “immortalised” as such, which served at the same time to make them appear taller and “in command” of something.

Travelling by horse has also been for a long time the fastest mode of transport, yet another symbol of social status used in media campaigns of those times. The memorials in honour of Marc Aurel had already during the ancient time the function to transmit an image, the emperor wanted history to keep in mind, rather than the view of ordinary people in the Roman empire. Memorials of political leaders have been a demonstration of power for centuries before and for centuries to come.

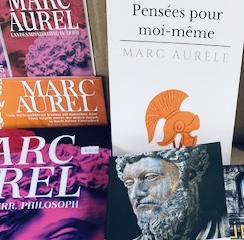

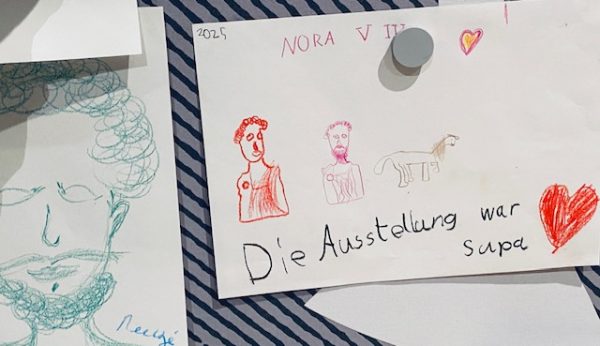

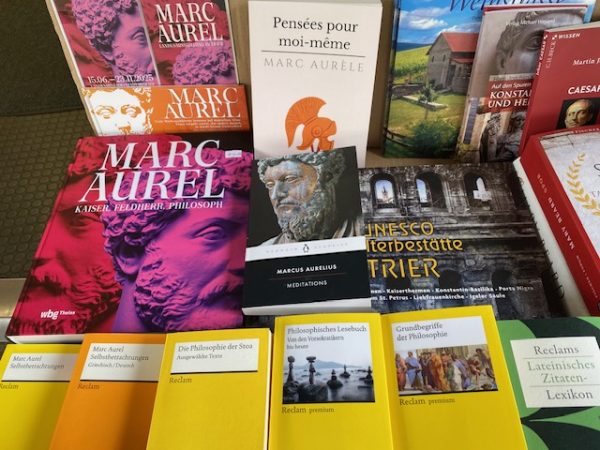

(Image: Trier Marc Aurel exhibitions 2025-9)